Structural sin

Cover image credit

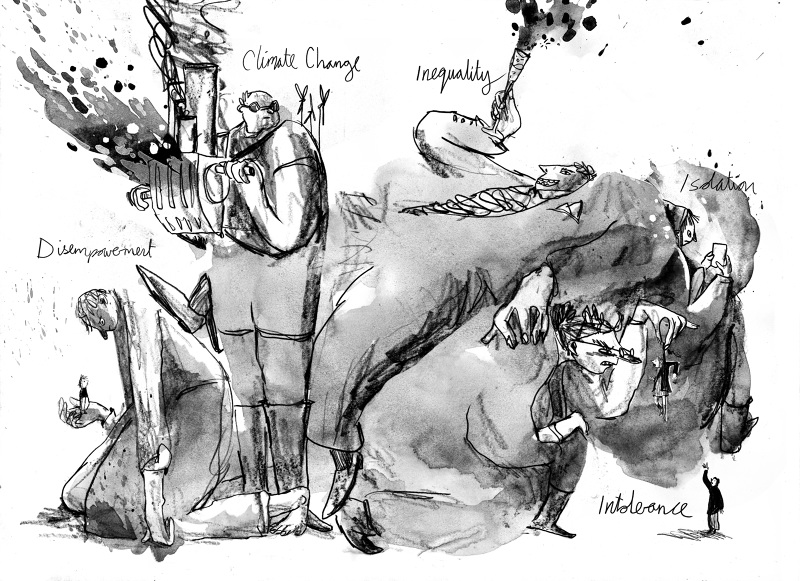

‘Five Giants’, Illustration by Josh Philip Saunders. Further details available at: https://joshphilipsaunders.co.uk/Five-Giants

Commissioned by the RSA for their work on ‘Britain’s New Giants’

Christianity needs a concept of structural sin

Many of the seemingly intractable problems we face as a society today, such as climate change, inequality, poverty and systemic racism, aren’t the result of any particularly bad or evil individuals. It is difficult to find the true culprits of these evils, but we know they are largely or wholly problems of humankind’s making.

For many people in the UK and indeed the western world, their ideas of good and evil are heavily influenced by Christianity, even if they are not religious. The Church teaches children that a sin is an act they do. Those children grow up into adults who don’t understand how they, without doing anything particularly evil themselves as an individual, can still be part of these much wider evils.

Stuck with an idea that we are only responsible for our own direct actions, we end up unable to deal with any problems that lie outside our most obvious responsibilities as a solitary individual.

The secular language of politics is slowly creating the language needed to understand these problems, with people talking about institutional, structural or systemic problems, though this isn’t without labour pains. The Church should not just keep up, but lead the way by identifying structural sins. Otherwise, our ability to respond to these problems will continue to be stunted by our failure to understand our role in them.

Praying as a child

Most children’s introduction to ethics is when they are told they can do ‘good’ or ‘bad’ things, and that they need to say sorry for those bad things. This is often framed in explicitly religious terms of sin, repentance and forgiveness. The language might be different for children brought up outside a religious background, but the lessons are the same.

I think the words children use, or are told to use, in their prayers are very telling. Children are taught to pray things like: ‘Please forgive me for calling Sally names and for annoying my sister, and look after people in Africa who don’t have enough food.’ There is a clear distinction in such prayers between their actions, falling into the realm of sin; and the far-off tragedies, falling into the realm of divine intervention.

It’s understandable that we only ask children to think about their own direct actions, because looking beyond this gets complicated, but nonetheless it remains a problem that from the earliest stage our concepts of evil are very much focused on the individual and their actions. Even when children are taught that their failures to act or omissions can be sinful, the focus is still on the failure of them as an individual to act.

Praying as an adult

As we grow older and more capable of understanding complex chains of causes and consequences, our view of moral responsibility should reflect this. Looking at the Anglican liturgy, I’m not sure that adults do much better than what is taught to children, as they are still focused on our actions or inactions as an individual:

‘We have sinned against you and against our neighbour, in what we have thought, in what we have said and done, through ignorance, through weakness, through our own deliberate fault.’

‘We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts. We have offended against your holy laws. We have left undone those things that we ought to have done; and we have done those things that we ought not to have done’

In defence of the liturgy, you can read the ‘we have’ as seeking forgiveness for sin we are part of as members of a society of community, and also the inclusion of ‘ignorance’ as an explanation is helpful. But I wouldn’t say that’s an obvious reading. Until I thought about it, I took the ‘we’ to be more simply just a reflection of the fact several people recite the prayer at once – in other words, it is a prayer by a collection of individuals not a collective.

Other key prayers aren’t much better, the Lord’s prayer mentions our trespasses and the trespasses of others against us, which to me sounds like we’re talking about us seeking forgiveness for committing evil acts as one individual against other individuals, and vice versa. It doesn’t capture a sense of wider societal evil. You can look at a whole range of prayers of confession online, and I haven’t yet spotted any that offer any obvious, explicit framework to think about societal evil or ‘structural sin’.

The corollary of leaving societal evils out of our prayers of penitence, is that when they do appear, they are treated as though they are tragic but natural disasters. We pray for some divine agency to intervene on all sorts of issues – poverty, war, disease – as though those problems have arisen spontaneously, like freak lightning strikes or volcanic eruptions.

We pray for them as though the world doesn’t have sufficient resources to meet everyone’s basic needs (it does), as though it isn’t in the power of governments and leaders to avoid violence (it’s difficult, but possible), and as though the treatments or preventions for many of these illnesses aren’t already discovered, known and available to us (they often are, but they’re too expensive for many of the people who need them).

The complexity of structural sin

Last June, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York (then John Sentamu) posted a statement on Facebook, calling racism ‘an affront to God’, acknowledging ‘continuing systemic racism’ and confessing that we all bear the responsibility to end this. While the Archbishops’ condemnation of racism seemed widely accepted, their use of the term ‘systemic racism’ caused consternation and affront to many commenters.

I was surprised by the strength of feeling I saw on this. It’s concerning that so many people in Britain are unpersuaded that structural racism is a problem and yet so deeply affronted by the suggestion. As Akala observes, ‘People get more upset by being called a racist than by racist things happening.’

People get offended by the discussion of structural racism because when they hear comments like ‘Britain is structurally racist’ they understand it as an accusation that they are a racist. Their first thought is of their own defence, ‘but I’m not a racist!’ and then defence of others, ‘no-one in my family is racist, and I think hardly any British people are racists.’ There is a dilemma between talking about structural racism in such an abstract detached way that people will just ignore it, or putting it in stark enough terms that people then feel society’s ills are being unfairly laid at their feet. Sometimes I wonder if it would help to add the caveat: ‘but this doesn’t mean that you individually are particularly racist’

How best to explain to people that living a ‘normal’ and good life as an individual, in a global system that is deeply unjust, will still mean in your own small, involuntary way you will be involved in perpetuating that system? For example, the Hostile Environment policy was an appalling and overt example of racism. I wasn’t personally responsible and it’s difficult to point to anyone in particular as wholly responsible. While the UK government makes the laws and policies, it governs on behalf of the public who elect them. And the public only vote occasionally, with limited information and options, not to mention that any one vote has only a miniscule impact on the outcome.

Admitting that responsibility for issues such as the Windrush scandal is diffuse and complex does not mean that it was a natural phenomenon beyond human control. This is where the concept of structural sin can be so helpful – it doesn’t demand that we are wracked with guilt on an individual level, but also doesn’t allow us to simply do nothing.

Environmentalism

Climate change and the impact of humanity on the environment is another issue that could helpfully be understood as ‘structural sin’. I took part in a study group at my east London church (liberal anglo-catholic) on the theme of ecological justice. We used the study materials published by the United Society Partners in Gospel, which are available online, and met via Zoom. I was impressed with these materials, which did not shy away from climate politics. The opening chapter included this message: ‘Growth remains the core objective for economic organisation, whilst this logic proposes that economic systems will collapse without the expansion of production and consumption’.

In one week of the course, the case study was set in the Philippines and described indigenous beliefs about respect for the environment. One indigenous population there understood nature to have a spiritual life of its own, and sought to live by the principle of ‘Inayan’ – that one must do to others, and to nature, as they would want to be done to themselves. A member of our parish discussion group was herself from the Philippines, and remembered that people would say ‘excuse me’ to a plant or animal if they had to step past it, as they would to a person. This made me think of fairy thorns back home in Northern Ireland – hawthorn trees supposedly protected by fairies (not the Disney type). Many people like me wouldn’t believe the superstitions, but would be uncomfortable wielding an axe to one! I think humankind has always had some discomfort with complete domination over their environment and these trees were our reluctant nod towards that.

The course materials didn’t talk about it explicitly, but it clearly invited parallels to be drawn about the colonial approach of domination and eradication to indigenous traditions and how global corporations dominate and destroy the environment in the countries where they site production. My Filipino friend concluded her reminiscing about people greeting the trees, saying, ‘of course, the people need jobs to live, and the corporations that create the jobs pay them to chop down those same trees and build factories.’

The best intentions of individuals can be so easily crushed by greater powers. I saw this play out before my eyes a few weeks ago, when my friends heard the fact that plastic straws make up just 0.03% of ocean plastic, while 46% of the floating plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch consists of industrial fishing nets. This fact was included in a new Netflix documentary film, ‘Seaspiracy’, about the environmental image of fishing, which has been very much the topic of millennial Zoom-parties and picnics. The film has graphic and shocking depictions of the killing of dolphins and whales, but the fact that really stuck with people was how small the impact of cutting out straws was compared to plastic from industrial fishing.

The discussion about the environment so often ends up focusing on what we can do as an individual, which has its place, but too often comes at the exclusion of calls for governments to do things that will actually be effective. And this misplaced focus suits those who benefit from the status quo – so it isn’t surprising that we’ve all heard more about eliminating plastic straws or eating less fish than we have about the fishing industry, or that columnists argue back and forth about how much shame we should feel for travelling by plane – but I’ve never seen a serious argument about simply banning private jet travel. As our understanding of moral responsibility and sin has been limited to our actions as an individual, so has our ambition for agency over the world.

Some signs of progress

There are signs that Christian Churches are beginning to learn from the new secular language of structural or systemic oppression, or are even rediscovering their own existing concepts.

In his 2013 Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis criticised the trickle-down theory of growth and what he calls the ‘sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system’ – saying that they have not succeeded in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness and that the excluded are still left waiting. The same document says that inequality creates ‘a state of social sin’. In a letter to David Cameron ahead of the G8 conference, Pope Francis wrote: ‘We have created new idols. The worship of the golden calf of old has found a new and heartless image in the cult of money and the dictatorship of an economy which is faceless and lacking any truly humane goal.’

Last year, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, The Archbishops of Canterbury and York (then John Sentamu) published a statement saying that racism was an affront to God, that ‘system racism’ continued and that all had a responsibility to tackle it. Not surprisingly, the use of the term systemic racism caused anger and consternation amongst some commenters, several of whom said that it was ‘marxist’ or a ‘hoax built by those replacing Jesus with Marx.’

It’s tempting to dismiss comments calling the Archbishop a Marxist as just online trolls, but it is telling that they have struck upon the exact same attack that is used against Pope Francis by his conservative critics. And indeed, it was this same attack used against Gustavo Gutierrez and liberation theologists in the 80s by Pope Francis’ predecessors. Under Pope John Paul II and the then Cardinal Ratzwinger, the writings of liberation theologists were investigated and in a subsequent Vatican report, Marxism was declared incompatible with Catholic teachings.

Most Christians fall under the myth that our economic system, the very existence of wealth and prices, is a natural inevitability. The fact our economy isn’t ‘planned’ by one person or government doesn’t mean that it isn’t created and sustained by humanity as a whole. We might not be deliberate or willing participants, but we are involved in sustaining it nonetheless.

Many Christians will hasten to add, rightly, that when they pray to God about these things, they do so knowing that these problems are, at least in the large part, created by humankind. Christians point out that their prayers are to transform humanity so we can deliver ourselves from these evils, and that praying about them is part of making that transformation.

That might be true to an extent, but why is it buried, tacitly, in the assumptions behind the prayer? If we don’t make our own social responsibility explicit, how do we expect that to percolate down into our own minds, or to our children? I strongly suspect that, subconsciously at least, most of us still feel like many of the greatest evils facing the planet are nothing to do with us at all.